Sometimes I Wish I Had Had an Abortion.

Recent Posts:

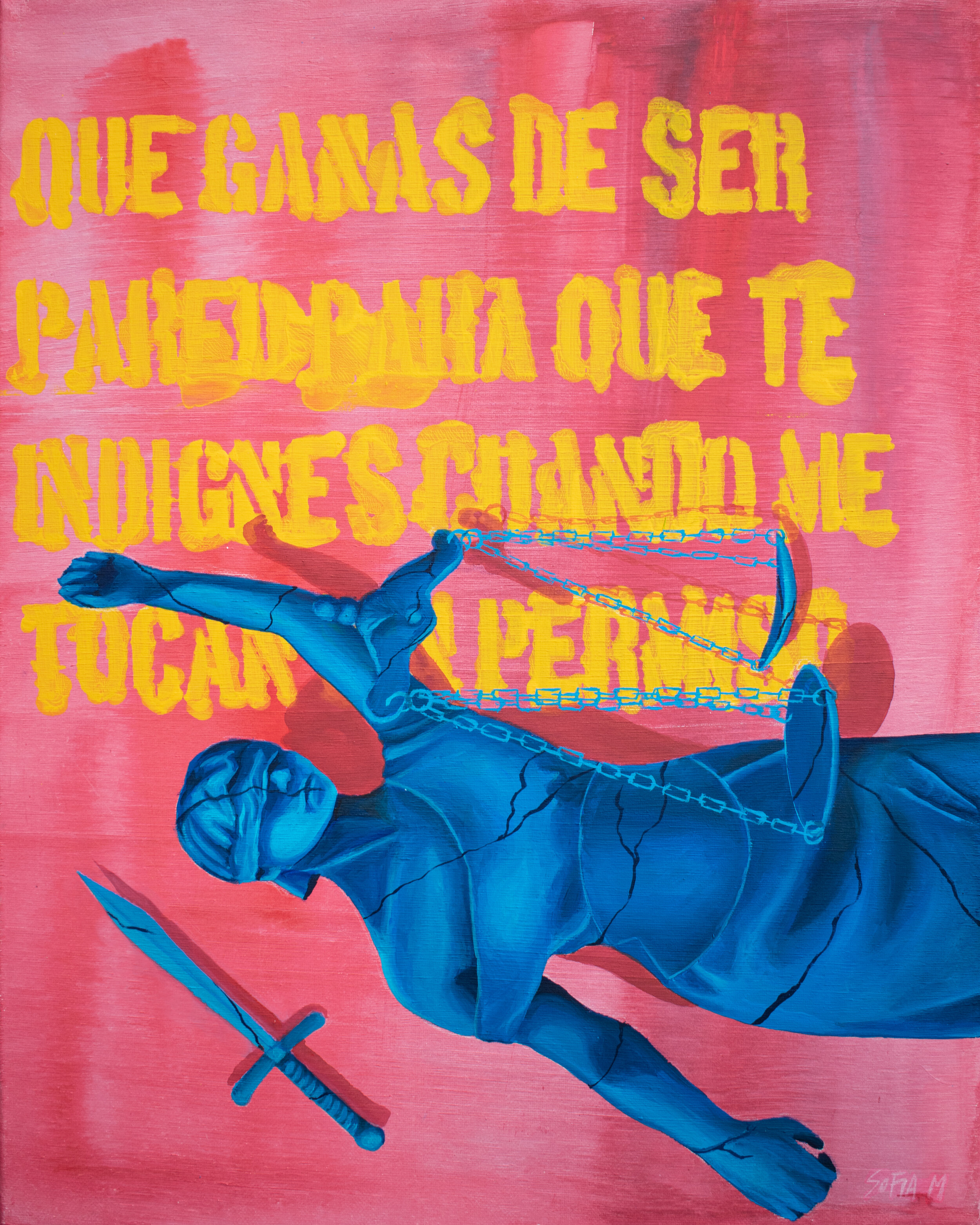

La Impunidad: Disposable Women and Inexcusable Crime

Art by Sofia Merino

On March 7th, 2017 the world awoke to a harrowing tale of 56 young girls burning inside an orphanage in Guatemala City, Guatemala. A nation already inundated with the burdens of gang violence, the news that broke that day reflected another, more insidious, form of brutality. This corrosive element has lurked in the background of Latinx politics at large since at least the 90s but this overt expression in Guatemala just before Women’s Day.

After a daring escape from their orphanage, the site of many traumatising acts, the girls were sequestered in a classroom by the police. With no permission to leave, the girls banded together to force the police to free them - they lit a mattress on fire. As the flames engulfed the room the police stood idly by allowing the brutal murder of 41 girls. This is the mark that Guatemala must bear. The blood of 41 young girls mars the hands of those officers. The burns that scar the skin of the living even moreso.

Years later no charges have been levied by the state, and many place the blame on the 15 girls that lived. The question is then begged - did their lives matter? Moreover, did their deaths?

The government made it clear that the answer is no. The weeks following the vicious act saw the government, headed by President Jimmy Morales, attempt to halt public mourning and dissent. These officers acted with impunity, an absolution from their acts granted to them by a justice system and a government entrenched in machismo.

Impunity has long been seen as a way of legitimizing violence, and when it comes to the violence enacted on women its role is immeasurable. Violence is often baked into the collective consciousness, the violence that we revile, the ones we condone, and the ones we endorse. Whether we think about it or not, we are constantly making allowances for the violence we see everyday, but sometimes the cruelty reaches a fever pitch.

The world stops, the people question, and the government makes a choice. In Guatemala the choice was clear, we stand with murderers not the murdered. To so boldly express a comfort with the flagrant acts of sadistic violence was a striking message for the thousands of other violent and hateful men that contribute to the nation’s atrocious femicide and gender-based violence rates.

Day in and day out the country’s justice system fails the thousands of women who have died and the millions who fear that fate. While the nation boasts the 7th highest femicide rates in the world the conviction rate for these crimes is dismal.

In 2008 the government actively changed the judicial process for the prosecution of crimes against women. At the time the changes were revered as a progressive way forward but just two years later it became apparent that something was amiss. The system that aimed to put women first still left over 99% of murderers unconvicted.

The question is why are perpetrators being absolved of their crimes?

Well, the answer is multifaceted. There are first financial barriers to accessing justice. The toll that legal fees take on the most affected communities cannot be neglected, especially in a country like Guatemala where inequality continues to skyrocket at a rate the government can’t possibly control. When women and the communities and families they belong to can’t access the justice system because of financial circumstances, it makes it impossible for justice to be carried out.

But even in highly publicised cases where lawyers are offering pro bono representation and people are fundraising by the millions, what happens? Where is the disconnect, what is halting justice?

Surely it can’t be the system itself, was specifically designed to benefit and support these women. If not the judicial process it must be the will of the people, it must be some unresolved resentment or conviction that keeps the judges, juries, and spectators from wielding the law for, and not against, the victims.

This culture of impunity incites crime. The violence, the fear, the impunity, it feels unstoppable because it is. Without punishment crime persists, indefinitely. Moreover, unpunished crime sends a message. These failures of the people, the government, and the system itself create a mosaic of severe injustice that perverts how the public understands crime as a whole.

Suddenly femicide is just something that happens, and again it filters into the background. All these acts we once thought too vile for cable news become movie titles and TV show plotlines. Yet another facet of life, yet another form of violence to accept, condone - even endorse.

At the state level this manifests in the impunity we see corroding our nations. In Latin America this results in thousands of unsolved and unmarked cases of femicide. For years, most countries failed to even have a category for these heinous crimes, even now that they do every level of the justice system continues to fail women dying at the expense of male ego and dominance.

Gender violence is both a mental and physical act. It is about how we think and why we can allow for gender based violence and femicide.

Mbembe first thought of necropolitics as a reaction to Focoult’s concepts of biopower. Asserting that the state not only necessitates and makes life possible, it also dictates how and who must die. Mbembe wrote about this in the context of late stage colonialism and colonial power, but necropolitics persist in every case of oppression.

In Guatemala, and more broadly with the region, it creates an air of disposability around women. When the state fails to give justice to the thousands of women who have died, it allows for their murder - encourages it even. It clearly says that women are who must die and at the hands of violent machista oppressor is how.

When those police officers made the active choice to sit idly by and allow those girls to burn to death they were empowered by decades of ignorance and allowances. The government had shown them, long before this moment, that it was comfortable with letting these acts slide. They were, in essence, perfect victims.

Young girls, with no family ties, and no clear futures. Nothing tethering them to the duties and responsibilities that crowd Latin femininity. Even if they had embodied that perfect image of "Una Buena Mujer", their deaths would be simply mourned by the state but not for the right reasons.

Art by Sofia Merino

All across Latin America, all across the world even, feminity is encumbered by notions of service and labour. At the same time in which labour is becoming increasingly decentralised, deregulated, and disposable. The free market has come to liberate us from basic understandings of human life. This liberation is coming at the cost of the bodies we see piling up in Guatemala and abroad.

Women are coming of age, and girls are coming into existence at a time where their lives have never meant less in the face of the cold unfeeling capitalist patriarchy. The question is not whether they will continue to die, it is whether their deaths will ever mean more than a headline.

The women on frontlines of this weaponization of machista culture are indigenous women. Existing on the intersection of such oppressed identities makes these women uniquely vulnerable to the boom and bust cycle that modern womanhood entails.

They are uniquely disposable because Guatemala has built a system that keeps them from participating in political and public life. After the tragic civil war that occured in the early 1960s to mid 1990s, that saw a (US backed) government cease the nation through a coup d’etat many indigenous peoples lost the necessary documents required for political participation. The then government specifically targeted leftist guerillas, indigenous, and rural communities to quell dissent against the neoliberal capitalist system they sought to impose.

With no way to run for office, vote, or truly be known as “Guatemalan” many indigenous women have fallen between the cracks. Just another way the state signals who must die, the erasure of these people from the Guatemalan identity pushes them out of the scope of community, of protection. That means more than just the formal protections of the state, the police, or the justice system, it extends into the social. The casual ways we attempt to protect and defend those we feel kinship with. It is clear that while the formal war is over, the fight for the extermination of indigenous peoples continues in the hearts of the bands of murderers forming misshapen guerrillas at night.

The marginalization of these women is necropolitics at work. The death tolls we are seeing climb, even in this time of great isolation, is evidence of its success.

Disposability is vital to understanding what anti-femicide activism is all about. Whether they are conscious of it or not the women who continue to pour into the streets, petition the government, and violently express their discontent are refuting a falsehood that has travelled the world long before they got here. Refusing any notion or understanding of their humanity that is rooted in temporary service and fleeting male pleasures. They are asserting their personhood in every way they can.

Indigenous feminists are at the forefront of this movement. An affront to the government, who under president Morales has called the feminist movement a public enemy. An affront to a society that would rather keep quiet. An affront to a culture that would see them dead before they see them as human. A fierce and formidable declaration that the nation can no longer hope to silence them. That they cannot hold back a wave of budding young feminists from standing up for themselves. Reflecting back to a machista society the very same foreboding assertiveness it has used against them.

As Pia Flores, a prominent Guatemalan journalist and feminist organizer, said in conversation with ReMezcla “Each of us resists in any way we can, every time we leave our homes”. That resistance is what keeps the state from winning.

Countless feminists movements have made their way to Guatemala, with each one women get one step closer to their future liberation. That oasis on the far side of the desert, what we all hope we will arrive at sooner rather than later. From #MeToo to “El Violador en Tu Camino” the power of global feminist organizing is perhaps best encapsulated by the fight in Guatemala. A mishmash of feminist movements that push the nation the precipice of freedom.

Impunity persists, but so does the resistance. A constant reminder that this fight won’t end until there is justice. Justice for those 41 girls that died and the over 2,500 that came after them. This nation can’t heal without resolution - with reckoning. This is what feminism in Guatemala has to be about, a constant search for reconciliation - an end to the violence.

Hayley is an emerging writer and journalist who works hard to create work that is fiercely feminist, anti racist and anti oppression on a whole. You can check out more of her work and content on her instagram @hayley.headley

Las Pandillas: Women on the Run

In 2018, as an abnormally large number of migrants marched to the US border, they couldn’t have known the hell that would soon befall them. Now, in 2020, the issue has fallen to the background of US politics and out of the public consciousness. Though the so-called “crisis” on the border remains a major challenge to women’s rights on both sides of the line.

The vast majority of migrants on the border are women and minors coming up from the Northern Triangle, a notoriously fraught region. The NTCA refers to the three most tumultuous and low-income countries south of Mexico - El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala. Two of the most significant challenges to progress and development in these three nations are economic inequality and gang violence. These are harshest on the women in the region. Domestic violence is endemic, and recent years have seen gangs deliberately targeting women and children to extort further the communities they torment.

Artwork by Lucia Torres

To get a better picture of the current violence that is so widespread in the region, we need to understand a bit of history. The area has been rife with political, socioeconomic, and colonial conflicts for centuries. Military coups and a series of US interventions have kept the region unstable for decades. Long before the gangs, social and economic inequality manifested in all-out civil wars as the poor attempted to usurp their elitist oppressors. The tale of violent conflict within the region is a long and complex one, but the critical event that most informs the turmoil we are seeing today began in the late 1970s in the streets of El Salvador.

Socioeconomic divides that began brewing long before the nation’s independence spilled over into the 1900s and manifested in an attempted coup in 1930. The failure left the poor and wounded under the toe of a brutal military force controlled by the elite they sought to overthrow. Tensions continued to rise, and a string of attempted coups and assassinations came to a head in 1979 when a leftist military junta seized control of the country. After they failed to fulfill their promises to the working class, the five largest guerillas rose up to fight off their new oppressor. Under the National Liberation Front banner, these guerillas began a conflict that soon plunged the nation into civil war.

The war dragged on until 1992, and by then, the country had been decimated. The blood of 75,000 Salvadorans marred the empty streets as El Salvador attempted to rebuild with a crippled population, no government, and no clear way forward. Hundreds of thousands of Salvadorans fled during the 12-year long war, many of them leaving their children and seeking out better lives elsewhere. They most commonly arrived on the US border; many of them crossed illegally after failing to claim asylum.

The US had played a significant role in the war itself, providing arms and funds for the authoritarian regime who they chose to legitimize. It was with US sponsored arms and training that the regime would go on to commit 85% of the atrocities against their own people in the war. Though they fueled the most severe human rights violations they felt they owed nothing to the Salvadorans at the border. Their ignorance and ineptitude in dealing with the thousands of people flowing into the country left these refugees destitute. Forced into poor neighborhoods with no papers and no ability to get them, they fended for themselves in inner cities riddled with the kind of organized gang violence that plagues El Salvador today.

These Los Angeles neighborhoods were the birthplace of Mara Salvatrucha and Barrio Deciocho, gangs that now sprawl across the NTCA. They had innocent beginnings. They were a way for the Salvadoran community to defend themselves from the surrounding gangs that frequently harassed them. However, they soon became full-fledged drug trafficking operations, and while they continued to protect their community, the lucrative business was attractive for all these fresh and jobless refugees.

In the early 90s, the Clinton administration pushed for tighter restrictions on refugees arriving to and currently living in the US. This came with a wave of negative attention that soon saw many gang members deported back to a home with no infrastructure. Deportations began in 1993, with just dozens of gang members, but only two years later, the Clinton administration had forcibly removed 780 members from the country.

They arrived to an El Salvador with no ability or will to monitor and control them. Their operations flourished. The wave of migrant parents fleeing and leaving their children behind had created thousands of orphans, and with little else to occupy their time and no family that was fit to provide, the gangs became their refuge. The country was littered with weaponry that soon fell into the hands of the warring gangs that began to carve up the country. In lieu of a formal policing force and a well-established government, with thousands of lost children and abandoned artillery in their midst, Barrio 18 and MS-13 soon became the most notorious gangs in the region, spreading across borders and becoming a powerful economic and societal force.

El Salvador was brought to the brink of disaster in 2015 as its murder rate spiked to 104 per 100,000. That was a wake-up call for the government. After a series of trial and error policies, attempts to control and quell the swell of gang violence are finally yielding success. But as the war on the gangs in the NTCA continues to rage on, and even if the government wins, the seeds of future class struggle have already been sown. Like the nations surrounding it, the country is burdened with the lasting impact of colonial and imperialist oppression.

Economic inequality across the world is rising, but it poses even greater stress on women and girls in the global south. Burdened with all that femininity carries everywhere; caring for children, being economically viable partners, and being good homemakers. The weight of womanhood is extra heavy on women who are attempting to make lives in impoverished neighbourhoods plagued by violent crime.

Gangs are a symbol of fear for every member of society, but women have been uniquely made targets of their brutal acts. Gender-based violence has become just another weapon in the toolbox, and the victimization of women has become imperative to territorial control and power.

Women have been forced into hiding. They barricade themselves in their homes, avoid public life, and are still expected to provide for their children. The obstacles are continuing to mount. Femicide rates in the NTCA, particularly in Honduras and El Salvador, are the worst in the world. In 2018, 6.8 of 100,00 women in El Salvador died - the highest femicide rate in the world at the time. In that same year, Honduras topped out at 5.1, while Guatemala saw 2 per 100,000 women die because of their gender. These crimes are ruthless. The thousands of women who were found to be victims of femicide were mutilated and often found to have experienced some form of sexual violence before their death.

Artwork by Lucia Torres

The UN has made many reports that cite gang violence as a key factor in these crimes. Yet, a culture of machismo that glorifies the oppression of women prevents the police and the government from addressing these issues in earnest. As these governments wrestle with gang violence, women’s causes routinely fall between the cracks. Their policies fail to intervene in the places women need community and government support.

Femicide is just the tip of the iceberg. The gangs have taken up a policy of forcibly “recruiting” women by making them “novias de la pandilla (girlfriends of the gang).” These relationships have been referred to as modern slavery, marked by sexual and physical violence. Las pandillas in the NTCA have been known to extort families by threatening to take their daughters. They often kidnap these girls with or without the money, making these young girls bargaining chips in this sick game of chance. In this unique context, women have become more than products; they are a currency that ensures community submission to gang rule.

The options are simple - flee or pay and hope for the best. As the economic situation worsens in the region, and governments remain incapable of containing, punishing, or even rehabilitating gang members, the second is no longer feasible.

Again, all eyes turn to the United States. A country whose increasingly limited and nationalistic rhetoric continues to shut the door in their faces. Migrants coming up from the NTCA know this. They are well aware of the politics at play in the US and the many challenges on their long journey. They are conscious that this path is laced with violence and their success (or lack thereof) is up to fate. Still, they leave not out of any genuinely independent will but out of necessity. Economic hardship, widespread gang violence, and the overwhelming sense that change will never have spurred them into action.

The journey northward is long and arduous. Migrants are guided by “coyotes,” people who have made it their life's work to smuggle hundreds of migrants each year from their nations to the US’s southern border. They charge thousands of USD to make you a part of their group and often raise the price at will. Many families save for years for the chance to send just one person to safety.

Millions of migrants make the trek each year from the NTCA to the US’s southern border. In 2019 it was projected that 1% of the population of Guatemala and Honduras would attempt to make it to the US border. Less than half of them will actually get asylum. The US government will repatriate the rest, but commonly migrants don’t get far enough to stake their claim.

Today, women and children are occupying the lion’s share of migrants showing up at the border. This is indicative of the violence they are facing at home and the many challenges they are facing to obtaining legal status in the US.

Under the Trump administration, both Mexico and the US have tightened their border security. As the US becomes more isolationist in its policies, it places increased pressure on its allies to do the same. The crackdowns on the Mexican border with Guatemala have forced refugees into even more perilous routes. In these areas, they face extortion from regional gangs, victimization by human traffickers that kidnap these women and girls for sexual and domestic servitude.

There isn’t enough being done to protect these women, and this isn’t work they can push for alone. This unique trap has been constructed around them for decades, and escaping won’t be easy. Both international and national efforts to protect these women have to be focused on them - not on the gangs, not on money, or immigration. It has to center on the women who are dying and being enslaved because it is only through giving them justice; we can show them that there is hope.

The situation in the NTCA is getting better, but the gangs are also getting smarter, and unlike the general public, they are watching every move the government makes. Whether it be more lax immigration policies or harsher anti-gang patrols - they are preparing for it. And that preparation only puts more stress on these women and their families.

What a woman has to be is constantly changing, but in the NTCA, it is unclear if womanhood will ever not be tied to victimhood. There is so much more to being a woman in a society primed and accepting of the violence it enacts against you. It requires a fortification of self, a bravery that is unfathomable to most. These women’s stories may never be told in full, but their experiences represent what most of us can see so clearly - there is no justice without care for women’s rights.

Hayley is an emerging writer and journalist who works hard to create work that is fiercely feminist, anti racist and anti oppression on a whole. You can check out more of her work and content on her instagram @hayley.headley

El Marianismo: The Trap of Latinx Femininity

About the double standards and traps of marianismo culture.

El marianismo, as defined by Evelyn Stevens is “the cult of feminine spiritual superiority”. While machismo elevates men to the detriment of men and women alike, Stevens argues that women are the sole beneficiaries of this ideology. Stevens fails, however, to acknowledge the ways in which marianismo traps women in behaviours that ultimately benefit men.

The story of how this myth or cult of imagery surrounding women began in the New World is still retold today. The church says that ten years after the conquistadors first set foot on Mexican soil, an indigenous convert saw a vision of the Holy Mother of God in Tepeyac just north of modern-day Mexico City.

Before colonisation, this area was a significant place of worship for the indigenous people, where they worshipped their own mother figure Tonantzin. One of the first converts to Catholicism renamed Juan Diego saw the image of the virgin mother in place of Tonantzin. When this happened the priests and the Pope upheld this apparition as a testament to the power of God.

Since then, Mestizo culture has rallied around this image of Our Lady of Guadalupe, turning it into a national icon. Later, when this apparition became the patroness of not only Mexico but the whole of Latin America, marianismo spread through the whole region.

Art by Natalia Tapia

This cult of feminine spiritual superiority manifests in the duty of a good woman.

Una Buena Mujer is one that fully embodies the image of the weeping mother, dutiful wife, and chaste daughter. These three dimensions govern much of what femininity meant and, in some places, still means in Mexico and Latin America. The belief that women have this spiritual superiority endows them with a heavy burden, that which they must carry with piety and grace. This comes with the recognition that men not only don’t have this same burden but are also not capable of handling this sacred duty.

It is the belief that men could never be held to the same standards as women gives them the leeway to be violent, insolent and unproductive while still maintaining their superiority. Under a system of marianismo, women are at once exalted and persecuted, trapped in this mantle of the virgin mother. While machismo is the “exaltation of the masculine to the detriment of the constitution and feminine essence”, marianismo is about the exaltation of the feminine in the service of men.

Una Buena Mujer doesn’t ask more of the men around her, she is submissive and accepting of their failures. As Stevens says in her paper: “Beneath the submissiveness, however, lies the strength of her conviction - shared by the entire society-- that men must be humored”. Women have been pictured in the region as the backbone of the society, filling in the gaps where the men in their lives falter. Yet, this is seen as her duty not her sacrifice. The problem of this myth, this cult of female superiority is that it is not to her benefit but to her detriment all the same.

Under a system of machismo, womanhood is a vehicle, a functional space in society. Women are first daughters, chase and meek. Then they are wives and dutiful homemakers. Until finally they are mothers pious, caring and grieving. The perfect image of the Virgin Mother herself. But what comes next? Where do they go after they have fulfilled their purpose? After they have long overstayed their welcome? They die.

Women exist in this macho society in relation to and for the pleasure of men. This is what life used looked like, especially in the underdeveloped Northern towns and villages. But the growing pressures of international debts, free trade agreements, and multinational corporations with shaky moral values have caught up with the developing nation.

The idea of “una buena mujer” is deeply entrenched in most of Latin America, and while many young women have begun to challenge it, in states like Chihuahua the most radical stance in opposition to this archetype is the image of the working woman.

One of the drivers of the violence in Juarez is the invasion of global capitalist structures that have expanded the role of women in the workforce. While in much of Mexico globalisation has brought with it widespread development and a movement towards social justice, in the north, it has given rise to a wave of violence that threatens to drown the women that live there.

The Maquiladora industry has swept over much of the northern states, as a part of the “Programa de Industrialización Fronteriza” (the Border Industrialisation Program or BIP). The industry is synonymous with Mexican manufacturing, and features a variety of assembly line factories producing a wide range of export goods. The industry exploded under this program which allowed for foreign (and local) businesses to import machinery and raw materials essentially duty-free to industrialise and further develop the country, but particularly Northern states like Chihuahua.

Before BIP was introduced in 1965, PRONAF, an initiative geared towards improving infrastructure and creating jobs in border states, led to the construction of huge factories. When la Programa de Industrialización Fronteriza was introduced, foreign manufacturers began to use it as a way to import raw materials and export consumer goods at lower prices than ever before.

Art by Natalia Tapia

In the new era of global free trade agreements, the introduction of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in the ’90s propelled this once small fledgling industry into the economic powerhouse we know it to be today. As more North American investors saw the opportunity that came with mostly duty-free raw materials and little import taxes, Maquiladoras became a major means of production for primarily exported goods. But the rapid expansion of commercial spaces and central Mexican populations has led these factory jobs to be relegated to the North.

The industry has shifted Mexico’s socioeconomic landscape, but its greatest impact has been on the women in cities like Juarez. BIP failed to improve infrastructure in the North, it failed to bring the radical development it promised, and where it aimed to bring better jobs it has instead brought a second wave of indentured servitude.

Most workers at these factories are young women, from rural areas that surround cities like Juarez. And they have been targeted for stepping outside of their traditional role as women. A role which is rooted in religious dogma and machista oppression. We cannot pretend that this role exists in a cultural vacuum, it is inherently cultural. Machismo and marianismo have combined in the society to put forth an image of womanhood that is purposefully one dimensional. It is that picture perfect image of the barefoot pregnant housewife that dominates the minds of the many men who are outraged by female participation in the workforce.

Wright, in her research into the femicides that have erupted post-NAFTA, claims that it is the devaluation of female work under this new capitalist structure that has further devalued their lives. They have been made pawns in the capitalist game of low starting costs and high profits that characterises the modern Maquiladora industry.

Life in the industry is, however, highly undesirable. Much of the social friction that comes with women taking up space in this sector is rooted in them stepping out of their traditional roles and family structures. Women in this industry have been reportedly paid 25% less than the minimum wage, many have had miscarriages attributed to the long hours of menial labour. What infuriates the men in the society is this sense that women are being ripped from their homes, their proper duties, to focus instead on the working world.

Women working in the Maquila industry put their lives on the line day in and day out. Immediately after the introduction of NAFTA which sparked this mass expansion of the industry in the 90’s, the homicide rate for women spiked by 600%. Every day as these women leave their homes in the early morning they feel the threat. As they make the march with the others in their communities and approach the company bus, they notice the women who went missing the night before. They know all too well that they could be next. And yet, they persist.

They don’t have many options.

They have already given up so much to simply be here. Leaving behind their families and communities to move to this new city and entering into this line of work the predicates on their oppression. The Maquila industry has incited the mass migration of vulnerable, poor, independent women to cities like Juarez.

Where they are then preyed on by two systems; one that turns their victimhood into profit and another that turns it into symbolism.

Late at night as shifts end there is little to protect these women. The city is underdeveloped, the buses run late and the street lights don’t work. There are men who see this as the perfect time to exact their revenge, release their anger, and express their frustrations. These murders are brutal. They are deliberate and painful, they leave the women’s bodies mangled and bruised.

While there is little consensus between NGOs, academics, and politicians on who exactly is responsible for these crimes, the guaranteed side effect of this industry’s expansion is the increased vulnerability of these women.

The system of capitalism that degrades these women, their labour and their economic value is the same system that degrades them culturally. It is a system that stands firm in the belief that women are superior in a singular dimension, the spiritual, and that men have dominion over all other dimensions in which people exist. Even that minor superiority diminishes, fading into the background of a world that is increasingly less focused on fate and more on profit.

Capitalism is a patriarchal invention, and the pressures of global capitalism have only come to further gendered divides, not close them. But as Stevens observed in her research Latinx women have long been silent, and as she argues, unaware of this oppression. This is the crux of the issue.

As these women step out of the mantel, that has secretly been their cage, they are grasping for feminist empowerment. Their work is degrading, their employers degrade them, but their empowerment is their financial freedom. The perpetrators of these crimes are well aware of what the working woman means, the power she holds.

These murders, whether they are truly serial killers or simply gang members, are targeting these women because they have so boldly taken this step. When women are stuck in the social construct of marianismo, they are also stuck in the exaltation it gives them. They are trapped by terms of praise, the sense of piety that ultimately oppresses them further.

Joining the workforce signifies a transition into the feminist culture that dominates in central Mexico. This minor empowerment and freedom is opening the door for Northern women to find the same emancipation from this subtle condemnation that so many of their compatriots have. With every protest, every riot, these women are firmly asserting themselves and affirming their human value.

Asserting a value that exists outside of the spiritual, that takes its form in those fields they have so frequently been shunned from. The act of working in this industry while it oppresses them in a way that is much more overt, it is allowing them the chance to gain access to that feminism which has been previously unknown to them. These women are becoming educated, financially liberated and firmly aware of their own oppression.

The infiltration of the Maquiladora industry into the fabric of the Mexican economy represents many new and formidable threats. But it also represents a time of great, incomprehensible change. The agency and bravery these women are expressing as they take these first unsure steps outside of this caging mantel of the virgin mother, are laying the foundation for change.

Many activist movements and organisations have started in protest of the murders and as a way of providing support to the victims of gender violence in their communities.. The groups of women that have started to highlight these issues and call out for their rights are worth reading and learning about. We at the Whorticulturalist encourage you to do so. Here are some links to NGOs and feminist collectives from Jurarez and other cities and areas in the North of Mexico:

Casa Amiga is an organisation that provides immediate aid to women suffering from the violence in Juarez. If you click the link you can donate directly to them via paypal.

Ni En More is an organisation of women in Juarez that are combating the format of maquila work directly, they produce textiles and clothing that are rooted in activist foundations. You can donate and learn more about them here.

Ella Tienen Nombre maps the femicides in Juarez, with data going back all the way to the 90’s. This is a great resource to stay up to date on the realities of the violence, and you can see all the amazing work that is being done here.

Hayley is an emerging writer and journalist who works hard to create work that is fiercely feminist, anti racist and anti oppression on a whole. You can check out more of her work and content on her instagram @hayley.headley

El Machismo: A Lethal Construction of Masculinity

El machismo is a colonial mark, a permanent stain on the once rich and equal cultures of the Americas. It is at the core of the violence, mistreatment, and murder we have witnessed erupt over the past few years. Machismo is about weakness and power, the dichotomy that exists between the two, and how we who exist in gender binaries fit into it. It too transcends class and racial boundaries; it condemns all things not male, white, or wealthy. It lives in the collective unconscious that has gone unchallenged and uncorrected for years.

In her paper “ Machismo y Violencia ”, Carmen Lugo defines machismo as:

“... the expression of the magnification of the masculine to the detriment of the constitution, the personality and the feminine essence; the exaltation of physical superiority, brute force and the legitimation of a stereotype that recreates and reproduces unjust power relations. "

“The expression of the magnification of the masculine to the detriment of the constitution, personality, and the feminine essence; the exaltation of physical superiority, brute force, and the legitimization of a stereotype that recreates and reproduces unjust power relations. "

It manifests in many different ways and truly is a global model of oppression. Better known in the West as “toxic masculinity”, machismo is simply a product of a patriarchal system that governs the basic and complex systems and societies we all exist in. Waxing and waning in the background of our interactions, breeding slowly but surely a culture of hating women.

Art by Lara Solis

And how then might we liberate ourselves from this inescapable model? How can we extricate ourselves, as women, from this transcendent oppression? Even if we can reject this system within ourselves, how do we go about unearthing the patriarchy from our country, from the men in our lives, from our systems of justice and education?

These are questions that feminist collectives have been endeavoring to answer for decades. LASTESIS offers one answer, through protest. When you are unheard and unrepresented you must take to the streets, voice your opinions so loudly they can not be ignored.

“El patriarcado es un juez

que nos juzga por nacer,

y nuestro castigo

es la violencia que no ves.”

These opening lines to the feminist song that electrified the streets of Santiago, Chile. First performed in front of La Moneda by a crowd of hundreds of empowered and enraged women, the now-infamous piece “El Violador en Tu Camino” has since been performed in countries half a world away. Its lyrics transcending time, place, and circumstance.

The sounds of this feminist anthem give us goosebumps, the fond and unfamiliar sensation of being fully expressed. Originally written in Chilean Spanish, the lyrics resonate regardless of understanding, regardless of culture or borders. Distance is not the defining factor. It is that widespread appeal that is eerie and encouraging.

“The patriarchy is a judge

The judges us for being born

And our punishment

Is the violence that you don’t see”

It captures the very soul of what it means to be a Latinx woman right now, to be oppressed - to be hunted.

Chile is often touted as one of the “best” countries in the region, being one of the wealthiest with the lowest homicide rate. But we often forget the other side of the narrative, that the nation is also the most unequal, that crimes that do occur are brutal and violent, and that all of this disproportionately impacts women.

A country that seems almost perpetually on the brink of revolution Chile, has been no stranger to the scourge of gender-based violence that has swept the continent. And these murders are becoming increasingly graphic. They seem less like apathetic killings and more like performance pieces. Warning signs, sirens that scream: your womanhood is dangerous and our manhood is predatory

A study done in 2017 proved that nearly 40% of women ages 16-65 have or continue to experience domestic violence. In 2019, the nation saw 45 women fall victim to the government’s strict definition of “femicide”. There is a threat looming in the background of this seemingly peaceful society. While the Chilean government overlooks these issues, women are dying from a culture that long predates the independence of the nation.

El violador eres tú.

Son los pacos,

los jueces,

el Estado,

el presidente.

El Estado opresor es un macho violador.

These, the most notorious lines from the epic performance piece changed forever the way some women came to understand the nature of their oppression.

“The r*pist is you

It is the police

The judges

The state

The president

The oppressive state is an (aggressive) male r*pist”

Protests are the language of the unheard and unwanted. They are meant to uplift the oppressed and shine a light on our oppressors. These lines are awakening women a world over to realities that they have known but never acknowledged before. Helping them realise the all too present truth: there is a system of men who work against us.

It is about more than just the aggressor in these crimes. It is also about the police who fail every year to actively seek out justice and shame women out of even trying to report. The judges who go against the best interest of the victim and prioritize the future, safety, and happiness of the men who violate and desecrate these women’s bodies. The state that narrows its definition of femicide and does the bare minimum to protect women. The president who seems more preoccupied with furthering inequalities than with saving the nearly 40% of women who are suffering in obscurity.

This oppressive state forces them to be victims in their own homes.

This song has changed the work of activists all over the region and has propelled femicide, sexual violence, and all other forms of gender-based violence to the forefront of activist political discourse. The awakening it has incited is shifting the sociopolitical landscape in which these women fight. Slowly tipping the scales in their favour.

In Chile, this has led to more laws intended to further the pursuit of justice. However, new policies like the “Street Respect Bill” lack enforcement and seem to be the government’s attempt to appease the international pressure to crack down on the issue rather than create systemic change. While the crime of femicide does carry with it a long sentence, Chile’s definition of the crime is decidedly narrow. Limiting it to exclusively intimate femicide, lowering their official numbers, and creating greater barriers to finding justice.

Art by Lara Solis

Many activists are quick to point out that laws don’t reform a macho society. There is no way to do that without first addressing that it is in fact a macho society. To confront that “el violador eres tu” (the rapist is you), to recognise that everyone is complicit and that their actions, culture, and mindsets need to be uprooted to make a change.

Machismo began in Latin America during the era of Spanish and Portuguese colonialism. Carmen Lugo says:

“La cultura indígena es destruida, sobre las ruinas de las pirámides se erigen ostentosas catedrales, se nos impone un idioma extraño, una religión ajena; el orden de valores, la cosmogonía indígena es destruida; aparece una nueva sociedad, una nueva cultura donde lo indígena y lo femenino son relegados, son inferiores. Esa ecuación inconsciente, lo índio-femenino, se transforma en aquello que le recuerda al criollo, al mestizo, su superioridad sobre el vencido.”

“The indigenous culture is destroyed, in the ruins of the pyramids they erected ostentatious cathedrals and imposed on us a strange language, an alien religion; the order of values, cosmogony of the indigenous [people] are destroyed; there appears a new society, a new culture where the indigenous and the feminine are relegated, are inferior. This unconscious equation transforms the indo-feminine into that which reminds the Creole [those of Spanish/Portuguese and African descent], the mestizo [those of Spanish/Portuguese and Indigenous descent], of their superiority over the defeated”

Much like racism, machismo doesn’t exist in the absence of the white European colonizer. The destruction of the indigenous cultures; the vicious slaughter of their people, the burning and destruction of their temples, and cultural artifacts were only superseded in brutality by the widespread sexual violence of the era. What they left behind was a societal structure that routinely demeans and dehumanises women.

How then does this same structure, that has yet to be deconstructed, parsed apart and rebuilt, claim to protect women?

Chilean society and by extension no Latin American society can’t claim to uphold the rights and interests of these women. They have a foundation that is specifically built upon the defeat of them to further the superiority of men.

Machismo is also about much more than systems, it is deeply entrenched in the culture. It is the casual and common dismissal of women. It is the constant jokes about their inferiority. Jokes and comments that seem small and insignificant are playing out in major ways. These minor, casual statements that stoke the flames of male egos and male violence.

It is about the life cycle of these ideas. Abusers hear jokes or throw away comments and they continue to abuse the women in their homes. These women hear the same jokes from ‘pillars of their community’ and instead of reporting it, instead of trying to seek out better, they remain silent. Convinced that they have no supporters, no allies, and no options. These pillars of the community continue to live in ignorance of the very real, violence that plagues their cities. We get no change and the simple fact is no law will break these cycles.

What these women need is to be freed from this sick oppressive culture. We cannot put another man on trial for these vicious crimes until we put this system on trial. We cannot seek out justice for another woman until we construct a system that will give it to her.

In understanding our complicity we might hope to educate ourselves. When we can finally comprehend the long previously untraversed road ahead, only then can we hope to bring change to the continent. To undo the centuries of suffering that began when Colon first tarnished Latinx soil with his flagpole. Only then can the region hope to heal.

LASTESIS finishes the song with these final lines, a mockery of the police anthem:

Sleep easy, innocent girl,

without worrying about the bandit,

that for your sweet and smiling dream

watch your carabinero lover.

Sleep peacefully innocent girl,

Without worrying about the bandit

Your dreams sweet and smiling

Are guarded by your carabineer [a type of 17th-century soldier] lover

To support LASTESIS check out their instagram and facebook pages.

Make a note of:

Today marks 47 years since the military coup that instated Pinochet's dictatorship in Chile. The dictatorship is a huge part of Chilean history and has forever changed its political landscape and its effects are still being felt today . We want to encourage everyone to take some time to learn about the dictatorship, here are some links to articles and projects that might help:

An art project to remember The Disappeared

Hayley is an emerging writer and journalist who works hard to create work that is fiercely feminist, anti racist and anti oppression on a whole. You can check out more of her work and content on her instagram @ hayley.headley

El Feminicidio: Redefining Womanhood and Female Activism in Mexico

Art by Sofia Vargas Aguayo

While millions of women in North America and Europe celebrated their women’s day with marches and fun social media posts, Mexico was learning what it meant to live without them. From Tijuana to Chetumal, the streets, subways, and offices of cities and towns all over the country were operating without women.

#UnDiaSinMujeres was a countrywide sit-in. Abandoned by their government and the international community these women have been left to defend themselves against a country of men that seem hellbent on their extermination. This day was meant to awaken the police, prosecutors, and politicians to the future of their nation. It was meant to help these powerful men (and women) realise the gravity of the situation at hand.

“To understand that a war has been brewing in our voluntary negligence. ”

El feminicidio or femicide has been a growing issue across Latin America, and the past few years have seen these rates skyrocket. In 2018, UN Women put out a report saying that every day 12 women die from femicide in Latin America and just a year later 2019 the numbers topped out at about 10 women per day in Mexico alone. The numbers are staggering, and everyone is looking for a place to pin the blame; a single point source to this corrosive societal pollutant.

All eyes are on Ciudad Juarez and they have been since the early 90s. Amnesty International has been calling out the dire circumstances in Juarez since 2005. They revealed that over 370 young women and girls had been murdered without justice or cause since 1993.

In a study of Ciudad Juarez, done as an analysis of a decades-long history of violence against women from 1993 to 2007, researchers identified that these offenses are primarily either intimate or systemic sexual femicide. Intimate refers to femicide that is perpetrated by someone close to the victim, while systemic sexual has its roots in patterns of violence against women and children like kidnapping and sexual assault. These two accounted for about 62% of all femicides in the city for that time. The pattern has since continued, with the bulk of women dying at the hands of violent men who knew them or men who simply saw them as yet another target. The only significant change is the sheer number of women who have fallen victim to these felonies.

While this city is best known for its reputation as the murder capital of the world or its features in shows like Narcos or El Chapo; it has an unspoken history of violence against women. It expands far beyond murder; it’s the hundreds of women that have gone missing since the 1990s, it’s the thousands of women who experience sexual violence every year, it’s the gross mistreatment of women and girls at home and in the streets.

Moreover, the situation is about more than just Juarez. It is easy to push the blame around, to try and localise the situation to one city or one state. But the reality is that femicide is on the rise all over Mexico, that 1.4 of 100,000 women die each year from these heinous acts of violence, that Mexico doesn’t even chart in the top 5 worldwide for these crimes. And it is the globalised nature of these issues that prompts us to ask the question - why? Why is any of this happening? Why is the situation in Mexico the way it is at all? Why does it continue and how did it start?

Some point towards the cartels and gangs that see women as cannon fodder for their wars. Others to a culture of machismo that has stoked the flames of the male egos in the region for decades. And a few try to point to simple circumstances, that there are thousands of people who die every year in Mexico… of course some women will be caught in the crossfire. But the fact is undeniable that women and girls are being deliberately targeted by vile men who seek them out, violate their bodies, and leave them there to be displayed like a flag, or a warning.

It is the impunity with which these murderers act that sickens me. It is the very fact that there is a system of people who fail every day to give these women the justice they deserve. After dying in such a graphic and brutal manner, the least the powers that be might offer is the meager gift of a sentence passed - a sliver of dignity.

Art by Sofia Vargas Aguayo

There is something eerily commonplace about these crimes. That is a part of their cultural danger. It is easy to get desensitized by these numbers and forget what they truly mean for the lives of millions of women and girls. It is easy to forget that day after day women turn on the news to hear of yet another young woman. One no different from themselves, no different from their sisters or daughters or mothers being slaughtered. But it is even easier to keep searching for an answer with no intent on finding one.

The women of this country know exactly why this is happening. They know how you can fix it, but they also know you refuse to listen. These women have been left to their own devices, to seek justice for themselves. Surely they are victims of a system and a society that sees them as nothing better than warm bodies or lambs to the slaughter but they have refused to trap themselves in their victimhood.

The mothers of the women who have died as a result of femicide have empowered themselves. In early 2020 one of them took it upon herself to confront her country and the murderers who reside there with a poignant question :

“Cual es tu pinche problema?”

“What is your fucking problem?”

In a speech that went viral, she spoke with a fury that I sincerely hope shakes the nation. She spoke from her heart, and she spoke for everyone in the same situation. She knows there is nowhere to turn in her fight for justice other than the public. Saying:

“Yo no soy una colectiva, ni necesito un tambor, ni necesito de un pinche partido político que me represente”

“I am not a collective, and I don’t need a drum, or a fucking political party to represent me”

She can represent herself. This organic, grassroots activism has been the largest, strongest and most public opposition that has been displayed amid this crisis. Movements like Ni Una Mas and #UnDiaSinMujeres have been central in these women’s fight to be represented and heard. But no matter how many protestors pour into the streets, or mothers share their stories, or women stay home, it is impossible to ignore that they first took to their stand in the 90s.

It has been 30 years since this became a national and regional talking point. 18 years since Mexican women first spoke up and said that not one more girl or young woman should share this fate, and yet thousands more bodies have been buried - victims of this savage and unprovoked violence.

The Mexican government only officially began to monitor femicide in 2012. Nonetheless in these 8 years it has offered little in the way of making practical amends. They have made special prosecutor offices and extended sentences, but femicide is still on the rise. After years of willful ignorance, feminists all over the country rejoiced in hope that their newest leftist president would turn the tide. But two years into his administration, next to nothing has been done. Activists and women all over the country are at a loss for what to do.

The world has told them over and over again that they are each other's only allies, in this fight for the basic right to life. And it is the basic right to exist, that is reaffirmed in every human rights agreement, every constitution, and law, that is being affronted in this subtle warfare. This conflict has taken thousands of lives and scarred tens of thousands more. It is ushering a new era of female fear.

For me, it is more terrifying to think that it will not be bringing with it a new era of women’s rights. Protests and riots have been reignited since the start of 2020, and while things have slowed due to the pandemic, these women are no less desperate and no less ready to fight. What happens over the coming months and years will forever reshape the geopolitical landscape in which we, as women, all continue to live in. It will forever change how and if women get to exist.

All over the continent rights are eroding and they are being repackaged and resold to us as privileges. It isn’t a privilege to narrowly escape death. There is no surplus in simply awaking each day. What wealth is found in existence under constant threat? These women are being offered their next breath as a gift from the state. The very same state that fails to uphold these most basic rights day in and day out.

Even so, these women have continued to persevere. Unashamed and unconstrained they stand up for themselves even if there is no one standing with them. There is something unique about Latin America’s revolutionary spirit. There is something special about the ability of these women to unify in their fear and anger. That spark, the fervour and zest with which they seek out a better life for themselves and their children, is invaluable.

Not much is certain for the future of femicide or feminism in the region, but one thing I am certain won’t be abandoned is this burning desire for change. It is impossible to know how many more protests will be held, or how many more days there will be where women disappear from the streets, or if sustainable change will come at all.

It is scary to think of what happens if this continues, or what it means to live in a world that doesn’t care if it does. El feminicidio is about more than just Mexican women, more than Latinx women, it is about the fate of womanhood everywhere. These women are fighting for a system that upholds more than just their rights, they are fighting for women’s rights everywhere.

How can you support them in this fight and get involved?

Check out and support local and regional activist organisations like:

Donate to organisations that support women’s rights and the women fighting for them:

Hayley is an emerging writer and journalist who works hard to create work that is fiercely feminist, anti racist and anti oppression on a whole. You can check out more of her work and content on her instagram @hayley.headley

Reap what you hoe.

Sign up with your email address to receive our latest blog posts, news, or opportunities.