Sometimes I Wish I Had Had an Abortion.

Recent Posts:

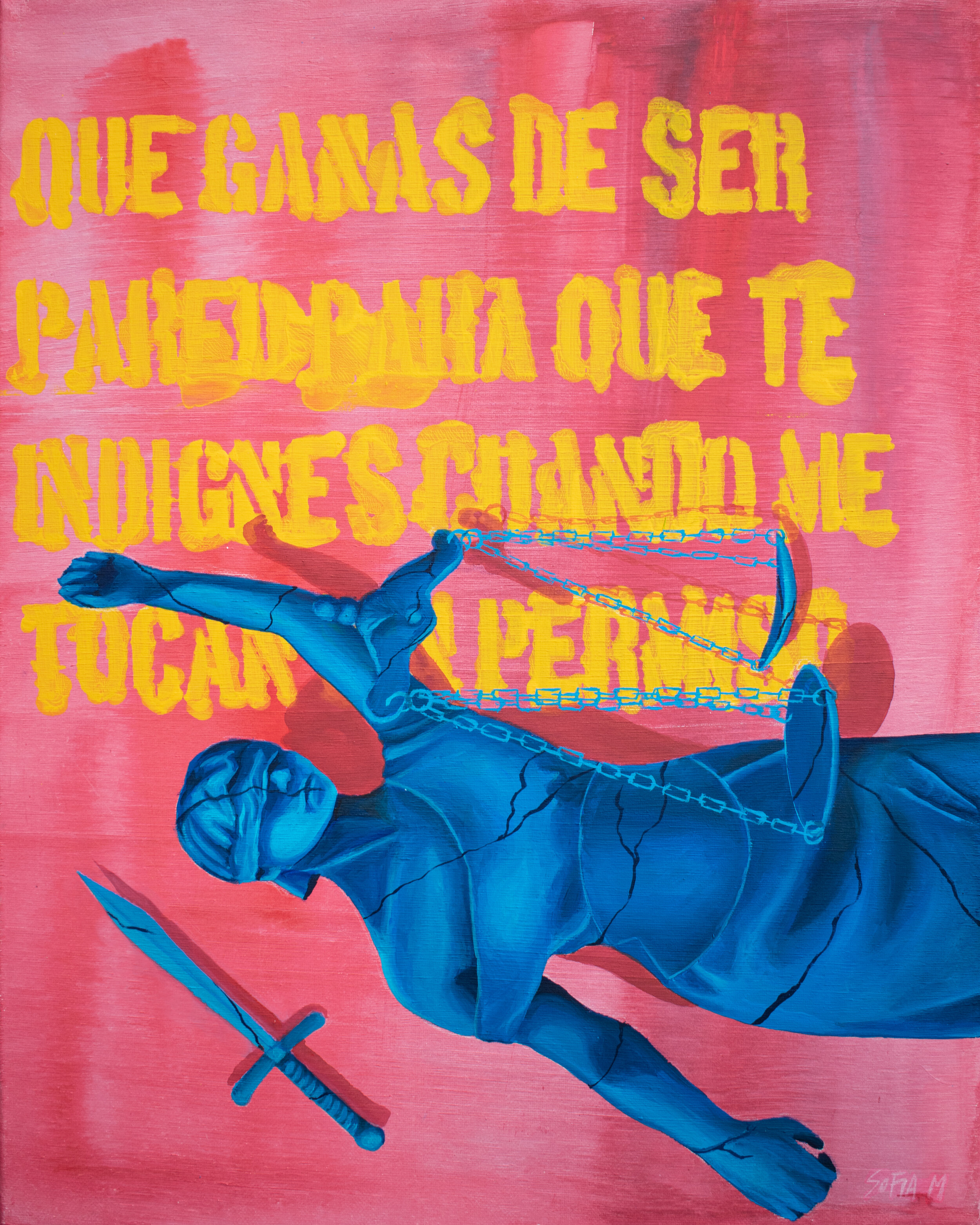

La Impunidad: Disposable Women and Inexcusable Crime

Art by Sofia Merino

On March 7th, 2017 the world awoke to a harrowing tale of 56 young girls burning inside an orphanage in Guatemala City, Guatemala. A nation already inundated with the burdens of gang violence, the news that broke that day reflected another, more insidious, form of brutality. This corrosive element has lurked in the background of Latinx politics at large since at least the 90s but this overt expression in Guatemala just before Women’s Day.

After a daring escape from their orphanage, the site of many traumatising acts, the girls were sequestered in a classroom by the police. With no permission to leave, the girls banded together to force the police to free them - they lit a mattress on fire. As the flames engulfed the room the police stood idly by allowing the brutal murder of 41 girls. This is the mark that Guatemala must bear. The blood of 41 young girls mars the hands of those officers. The burns that scar the skin of the living even moreso.

Years later no charges have been levied by the state, and many place the blame on the 15 girls that lived. The question is then begged - did their lives matter? Moreover, did their deaths?

The government made it clear that the answer is no. The weeks following the vicious act saw the government, headed by President Jimmy Morales, attempt to halt public mourning and dissent. These officers acted with impunity, an absolution from their acts granted to them by a justice system and a government entrenched in machismo.

Impunity has long been seen as a way of legitimizing violence, and when it comes to the violence enacted on women its role is immeasurable. Violence is often baked into the collective consciousness, the violence that we revile, the ones we condone, and the ones we endorse. Whether we think about it or not, we are constantly making allowances for the violence we see everyday, but sometimes the cruelty reaches a fever pitch.

The world stops, the people question, and the government makes a choice. In Guatemala the choice was clear, we stand with murderers not the murdered. To so boldly express a comfort with the flagrant acts of sadistic violence was a striking message for the thousands of other violent and hateful men that contribute to the nation’s atrocious femicide and gender-based violence rates.

Day in and day out the country’s justice system fails the thousands of women who have died and the millions who fear that fate. While the nation boasts the 7th highest femicide rates in the world the conviction rate for these crimes is dismal.

In 2008 the government actively changed the judicial process for the prosecution of crimes against women. At the time the changes were revered as a progressive way forward but just two years later it became apparent that something was amiss. The system that aimed to put women first still left over 99% of murderers unconvicted.

The question is why are perpetrators being absolved of their crimes?

Well, the answer is multifaceted. There are first financial barriers to accessing justice. The toll that legal fees take on the most affected communities cannot be neglected, especially in a country like Guatemala where inequality continues to skyrocket at a rate the government can’t possibly control. When women and the communities and families they belong to can’t access the justice system because of financial circumstances, it makes it impossible for justice to be carried out.

But even in highly publicised cases where lawyers are offering pro bono representation and people are fundraising by the millions, what happens? Where is the disconnect, what is halting justice?

Surely it can’t be the system itself, was specifically designed to benefit and support these women. If not the judicial process it must be the will of the people, it must be some unresolved resentment or conviction that keeps the judges, juries, and spectators from wielding the law for, and not against, the victims.

This culture of impunity incites crime. The violence, the fear, the impunity, it feels unstoppable because it is. Without punishment crime persists, indefinitely. Moreover, unpunished crime sends a message. These failures of the people, the government, and the system itself create a mosaic of severe injustice that perverts how the public understands crime as a whole.

Suddenly femicide is just something that happens, and again it filters into the background. All these acts we once thought too vile for cable news become movie titles and TV show plotlines. Yet another facet of life, yet another form of violence to accept, condone - even endorse.

At the state level this manifests in the impunity we see corroding our nations. In Latin America this results in thousands of unsolved and unmarked cases of femicide. For years, most countries failed to even have a category for these heinous crimes, even now that they do every level of the justice system continues to fail women dying at the expense of male ego and dominance.

Gender violence is both a mental and physical act. It is about how we think and why we can allow for gender based violence and femicide.

Mbembe first thought of necropolitics as a reaction to Focoult’s concepts of biopower. Asserting that the state not only necessitates and makes life possible, it also dictates how and who must die. Mbembe wrote about this in the context of late stage colonialism and colonial power, but necropolitics persist in every case of oppression.

In Guatemala, and more broadly with the region, it creates an air of disposability around women. When the state fails to give justice to the thousands of women who have died, it allows for their murder - encourages it even. It clearly says that women are who must die and at the hands of violent machista oppressor is how.

When those police officers made the active choice to sit idly by and allow those girls to burn to death they were empowered by decades of ignorance and allowances. The government had shown them, long before this moment, that it was comfortable with letting these acts slide. They were, in essence, perfect victims.

Young girls, with no family ties, and no clear futures. Nothing tethering them to the duties and responsibilities that crowd Latin femininity. Even if they had embodied that perfect image of "Una Buena Mujer", their deaths would be simply mourned by the state but not for the right reasons.

Art by Sofia Merino

All across Latin America, all across the world even, feminity is encumbered by notions of service and labour. At the same time in which labour is becoming increasingly decentralised, deregulated, and disposable. The free market has come to liberate us from basic understandings of human life. This liberation is coming at the cost of the bodies we see piling up in Guatemala and abroad.

Women are coming of age, and girls are coming into existence at a time where their lives have never meant less in the face of the cold unfeeling capitalist patriarchy. The question is not whether they will continue to die, it is whether their deaths will ever mean more than a headline.

The women on frontlines of this weaponization of machista culture are indigenous women. Existing on the intersection of such oppressed identities makes these women uniquely vulnerable to the boom and bust cycle that modern womanhood entails.

They are uniquely disposable because Guatemala has built a system that keeps them from participating in political and public life. After the tragic civil war that occured in the early 1960s to mid 1990s, that saw a (US backed) government cease the nation through a coup d’etat many indigenous peoples lost the necessary documents required for political participation. The then government specifically targeted leftist guerillas, indigenous, and rural communities to quell dissent against the neoliberal capitalist system they sought to impose.

With no way to run for office, vote, or truly be known as “Guatemalan” many indigenous women have fallen between the cracks. Just another way the state signals who must die, the erasure of these people from the Guatemalan identity pushes them out of the scope of community, of protection. That means more than just the formal protections of the state, the police, or the justice system, it extends into the social. The casual ways we attempt to protect and defend those we feel kinship with. It is clear that while the formal war is over, the fight for the extermination of indigenous peoples continues in the hearts of the bands of murderers forming misshapen guerrillas at night.

The marginalization of these women is necropolitics at work. The death tolls we are seeing climb, even in this time of great isolation, is evidence of its success.

Disposability is vital to understanding what anti-femicide activism is all about. Whether they are conscious of it or not the women who continue to pour into the streets, petition the government, and violently express their discontent are refuting a falsehood that has travelled the world long before they got here. Refusing any notion or understanding of their humanity that is rooted in temporary service and fleeting male pleasures. They are asserting their personhood in every way they can.

Indigenous feminists are at the forefront of this movement. An affront to the government, who under president Morales has called the feminist movement a public enemy. An affront to a society that would rather keep quiet. An affront to a culture that would see them dead before they see them as human. A fierce and formidable declaration that the nation can no longer hope to silence them. That they cannot hold back a wave of budding young feminists from standing up for themselves. Reflecting back to a machista society the very same foreboding assertiveness it has used against them.

As Pia Flores, a prominent Guatemalan journalist and feminist organizer, said in conversation with ReMezcla “Each of us resists in any way we can, every time we leave our homes”. That resistance is what keeps the state from winning.

Countless feminists movements have made their way to Guatemala, with each one women get one step closer to their future liberation. That oasis on the far side of the desert, what we all hope we will arrive at sooner rather than later. From #MeToo to “El Violador en Tu Camino” the power of global feminist organizing is perhaps best encapsulated by the fight in Guatemala. A mishmash of feminist movements that push the nation the precipice of freedom.

Impunity persists, but so does the resistance. A constant reminder that this fight won’t end until there is justice. Justice for those 41 girls that died and the over 2,500 that came after them. This nation can’t heal without resolution - with reckoning. This is what feminism in Guatemala has to be about, a constant search for reconciliation - an end to the violence.

Hayley is an emerging writer and journalist who works hard to create work that is fiercely feminist, anti racist and anti oppression on a whole. You can check out more of her work and content on her instagram @hayley.headley

Las Pandillas: Women on the Run

In 2018, as an abnormally large number of migrants marched to the US border, they couldn’t have known the hell that would soon befall them. Now, in 2020, the issue has fallen to the background of US politics and out of the public consciousness. Though the so-called “crisis” on the border remains a major challenge to women’s rights on both sides of the line.

The vast majority of migrants on the border are women and minors coming up from the Northern Triangle, a notoriously fraught region. The NTCA refers to the three most tumultuous and low-income countries south of Mexico - El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala. Two of the most significant challenges to progress and development in these three nations are economic inequality and gang violence. These are harshest on the women in the region. Domestic violence is endemic, and recent years have seen gangs deliberately targeting women and children to extort further the communities they torment.

Artwork by Lucia Torres

To get a better picture of the current violence that is so widespread in the region, we need to understand a bit of history. The area has been rife with political, socioeconomic, and colonial conflicts for centuries. Military coups and a series of US interventions have kept the region unstable for decades. Long before the gangs, social and economic inequality manifested in all-out civil wars as the poor attempted to usurp their elitist oppressors. The tale of violent conflict within the region is a long and complex one, but the critical event that most informs the turmoil we are seeing today began in the late 1970s in the streets of El Salvador.

Socioeconomic divides that began brewing long before the nation’s independence spilled over into the 1900s and manifested in an attempted coup in 1930. The failure left the poor and wounded under the toe of a brutal military force controlled by the elite they sought to overthrow. Tensions continued to rise, and a string of attempted coups and assassinations came to a head in 1979 when a leftist military junta seized control of the country. After they failed to fulfill their promises to the working class, the five largest guerillas rose up to fight off their new oppressor. Under the National Liberation Front banner, these guerillas began a conflict that soon plunged the nation into civil war.

The war dragged on until 1992, and by then, the country had been decimated. The blood of 75,000 Salvadorans marred the empty streets as El Salvador attempted to rebuild with a crippled population, no government, and no clear way forward. Hundreds of thousands of Salvadorans fled during the 12-year long war, many of them leaving their children and seeking out better lives elsewhere. They most commonly arrived on the US border; many of them crossed illegally after failing to claim asylum.

The US had played a significant role in the war itself, providing arms and funds for the authoritarian regime who they chose to legitimize. It was with US sponsored arms and training that the regime would go on to commit 85% of the atrocities against their own people in the war. Though they fueled the most severe human rights violations they felt they owed nothing to the Salvadorans at the border. Their ignorance and ineptitude in dealing with the thousands of people flowing into the country left these refugees destitute. Forced into poor neighborhoods with no papers and no ability to get them, they fended for themselves in inner cities riddled with the kind of organized gang violence that plagues El Salvador today.

These Los Angeles neighborhoods were the birthplace of Mara Salvatrucha and Barrio Deciocho, gangs that now sprawl across the NTCA. They had innocent beginnings. They were a way for the Salvadoran community to defend themselves from the surrounding gangs that frequently harassed them. However, they soon became full-fledged drug trafficking operations, and while they continued to protect their community, the lucrative business was attractive for all these fresh and jobless refugees.

In the early 90s, the Clinton administration pushed for tighter restrictions on refugees arriving to and currently living in the US. This came with a wave of negative attention that soon saw many gang members deported back to a home with no infrastructure. Deportations began in 1993, with just dozens of gang members, but only two years later, the Clinton administration had forcibly removed 780 members from the country.

They arrived to an El Salvador with no ability or will to monitor and control them. Their operations flourished. The wave of migrant parents fleeing and leaving their children behind had created thousands of orphans, and with little else to occupy their time and no family that was fit to provide, the gangs became their refuge. The country was littered with weaponry that soon fell into the hands of the warring gangs that began to carve up the country. In lieu of a formal policing force and a well-established government, with thousands of lost children and abandoned artillery in their midst, Barrio 18 and MS-13 soon became the most notorious gangs in the region, spreading across borders and becoming a powerful economic and societal force.

El Salvador was brought to the brink of disaster in 2015 as its murder rate spiked to 104 per 100,000. That was a wake-up call for the government. After a series of trial and error policies, attempts to control and quell the swell of gang violence are finally yielding success. But as the war on the gangs in the NTCA continues to rage on, and even if the government wins, the seeds of future class struggle have already been sown. Like the nations surrounding it, the country is burdened with the lasting impact of colonial and imperialist oppression.

Economic inequality across the world is rising, but it poses even greater stress on women and girls in the global south. Burdened with all that femininity carries everywhere; caring for children, being economically viable partners, and being good homemakers. The weight of womanhood is extra heavy on women who are attempting to make lives in impoverished neighbourhoods plagued by violent crime.

Gangs are a symbol of fear for every member of society, but women have been uniquely made targets of their brutal acts. Gender-based violence has become just another weapon in the toolbox, and the victimization of women has become imperative to territorial control and power.

Women have been forced into hiding. They barricade themselves in their homes, avoid public life, and are still expected to provide for their children. The obstacles are continuing to mount. Femicide rates in the NTCA, particularly in Honduras and El Salvador, are the worst in the world. In 2018, 6.8 of 100,00 women in El Salvador died - the highest femicide rate in the world at the time. In that same year, Honduras topped out at 5.1, while Guatemala saw 2 per 100,000 women die because of their gender. These crimes are ruthless. The thousands of women who were found to be victims of femicide were mutilated and often found to have experienced some form of sexual violence before their death.

Artwork by Lucia Torres

The UN has made many reports that cite gang violence as a key factor in these crimes. Yet, a culture of machismo that glorifies the oppression of women prevents the police and the government from addressing these issues in earnest. As these governments wrestle with gang violence, women’s causes routinely fall between the cracks. Their policies fail to intervene in the places women need community and government support.

Femicide is just the tip of the iceberg. The gangs have taken up a policy of forcibly “recruiting” women by making them “novias de la pandilla (girlfriends of the gang).” These relationships have been referred to as modern slavery, marked by sexual and physical violence. Las pandillas in the NTCA have been known to extort families by threatening to take their daughters. They often kidnap these girls with or without the money, making these young girls bargaining chips in this sick game of chance. In this unique context, women have become more than products; they are a currency that ensures community submission to gang rule.

The options are simple - flee or pay and hope for the best. As the economic situation worsens in the region, and governments remain incapable of containing, punishing, or even rehabilitating gang members, the second is no longer feasible.

Again, all eyes turn to the United States. A country whose increasingly limited and nationalistic rhetoric continues to shut the door in their faces. Migrants coming up from the NTCA know this. They are well aware of the politics at play in the US and the many challenges on their long journey. They are conscious that this path is laced with violence and their success (or lack thereof) is up to fate. Still, they leave not out of any genuinely independent will but out of necessity. Economic hardship, widespread gang violence, and the overwhelming sense that change will never have spurred them into action.

The journey northward is long and arduous. Migrants are guided by “coyotes,” people who have made it their life's work to smuggle hundreds of migrants each year from their nations to the US’s southern border. They charge thousands of USD to make you a part of their group and often raise the price at will. Many families save for years for the chance to send just one person to safety.

Millions of migrants make the trek each year from the NTCA to the US’s southern border. In 2019 it was projected that 1% of the population of Guatemala and Honduras would attempt to make it to the US border. Less than half of them will actually get asylum. The US government will repatriate the rest, but commonly migrants don’t get far enough to stake their claim.

Today, women and children are occupying the lion’s share of migrants showing up at the border. This is indicative of the violence they are facing at home and the many challenges they are facing to obtaining legal status in the US.

Under the Trump administration, both Mexico and the US have tightened their border security. As the US becomes more isolationist in its policies, it places increased pressure on its allies to do the same. The crackdowns on the Mexican border with Guatemala have forced refugees into even more perilous routes. In these areas, they face extortion from regional gangs, victimization by human traffickers that kidnap these women and girls for sexual and domestic servitude.

There isn’t enough being done to protect these women, and this isn’t work they can push for alone. This unique trap has been constructed around them for decades, and escaping won’t be easy. Both international and national efforts to protect these women have to be focused on them - not on the gangs, not on money, or immigration. It has to center on the women who are dying and being enslaved because it is only through giving them justice; we can show them that there is hope.

The situation in the NTCA is getting better, but the gangs are also getting smarter, and unlike the general public, they are watching every move the government makes. Whether it be more lax immigration policies or harsher anti-gang patrols - they are preparing for it. And that preparation only puts more stress on these women and their families.

What a woman has to be is constantly changing, but in the NTCA, it is unclear if womanhood will ever not be tied to victimhood. There is so much more to being a woman in a society primed and accepting of the violence it enacts against you. It requires a fortification of self, a bravery that is unfathomable to most. These women’s stories may never be told in full, but their experiences represent what most of us can see so clearly - there is no justice without care for women’s rights.

Hayley is an emerging writer and journalist who works hard to create work that is fiercely feminist, anti racist and anti oppression on a whole. You can check out more of her work and content on her instagram @hayley.headley

La Violencia Simbólica: Undoing the Myth of Passion Killings

The brutal murder of Chiara Páez by her boyfriend sparked the beginning of the feminist movement of “Ni Una Menos” in Argentina. Her body was found buried outside of her boyfriend’s home; Chiara was just 14, she was pregnant and scared, and she was murder by the father of her would-be child.

That was just the surface; as the trial unfolded, the details of her suffering rapted the country with intrigue. Only twenty hours into the investigation, her 16 year old boyfriend confessed. He told his father everything, how he forced her to take an abortion pill, how he killed her, and how he buried her and misled detectives by tampering with her phone. He confessed to all of it, and he told the police the same thing when his father brought him to the station later that day.

Yet, armed with all of this knowledge, the judge sentenced this boy to just 21 years. The penal code in Argentina would have allowed the judge to pursue a life sentence, to threaten him with the same loss of life, but instead, he gave him another chance. A clear path to freedom. The judge said that he based his ruling on the perpetrator’s demonstrated guilt and remorse.

The murder of Chiara began the movement, which soon spread across the whole continent. “Ni Una Menos” has been one of the most well-known forms of resistance against femicide. While it started in Argentina, it has inspired many other feminists in the region to begin their fight. Her death was a wake-up call for the nation, a big red flag that called into question much more than femicide but the state of women’s rights all over the country.

There was something special about her death, something that shook the core of Argentina. Maybe it was the fear that laid dormant in every mother that their sons could be so cruel or the shock at someone so young following in the footsteps of the hundreds of men that had the same thing. Maybe they realized they had let these sentiments fester for far too long, and this was just the manifestation of that. No one can be sure, but feminists all over Argentina were happy to be supported, and that June, the first march for the “Ni Una Menos” movement was held.

Art by Manu Ka

What the people didn't know - what they couldn’t until now was that they built around their sons, a society that breeds male violence. Moreover, one that entices us to accept it and be complicit in the actions of patriarchal and structural violence. Piere Bordieu first theorized of la violencia simbolica, or symbolic violence, and it describes perfectly the way patriarchal oppression is built into our language, customs, and worldviews.

For this article, I had the chance to talk with Ornela. She works with the NGO FENA in Argentina to combat the narratives that symbolic violence creates. She described symbolic violence as:

“[La violencia simbólica] básicamente son un montón de prácticas sociales, culturales, psicológicas que lo que hacen sentar las bases para que las otras formas de violencia sean posibles. La violencia simbólica es la primera de todas las violencias en tanto es la que permite construir la creencia de que alguien vale menos que las otras personas. ”

“Symbolic violence is a bunch of social, cultural, and psychological practices that lay the groundwork for other forms of violence to be possible. Symbolic violence is the first of all the acts of violence as it allows someone to think that they are worth less than others.”

It is about the small ways we, as a society, not just allow for violence against women but also incite and normalize that violence. It is the understanding that men have unearned ownership over women’s bodies. It is embedded in the very fabric of so many societies globally.

It is the reason that a young man felt he could unilaterally decide that his young girlfriend should have an abortion. It is the reason that he could ever envision murdering her. The same reason the judge’s ruling on this case came years later spat in the face of all of the goodness that sprouted from this tragedy—another notch on the belt of female oppression.

To say so boldly that you know what was done and you understand its wrongfulness has been proven beyond a reasonable doubt, and yet find it within yourself to give this boy mercy. It makes a mockery of her suffering, and it fuels a global narrative that seeks to normalize and legitimize male violence.

Symbolic violence is vital to understanding the whole iceberg of violence against women, as Ornela said: “El feminicidio es la más terrible de todas las formas de violencia que pueden haber contra una mujer: significa matarla por su condición de mujer”

“Femicide is the most terrible of all the forms of violence against women: killing her just for being a woman.”

A big part of FENA, and by extension, the work of all feminist collectives in the country, is making women aware of this. Symbolic violence is insidious, and it is that embedded nature that makes it so corrosive. It encourages women to internalize and accept their oppression.

Ornela summed this up perfectly, saying;

“Si en un lado tengo a una persona que no creo que sea superior a mí, y yo, al mismo tiempo, no me creo inferior a esa otra persona es bastante difícil que esa persona me oprima”

“If, on one side, I have a person that I don’t think is superior to me, and I don’t think I am inferior to this other person, it is very difficult for that person to oppress me.”

The problem is that there are messages everywhere in the patriarchal system that holds dominion over much of Argentinian society. At every turn, whether it is in your classroom, at home, or on TV, women are encouraged to be complicit in their oppression. Ornela puts this into context, with particular reference to the jokes that are prevalent in Latinx society:

“Todo lo que tiene que ver con la creación de los chistes, de las normas, de los lugares comunes, de las imágenes que nos vemos, de los mensajes que consumimos.”

“Everything that has to do with the creation of jokes, norms, common places, the images that we see, and the messages we consume.”

The implicit message women are seeing is that their bodies are not their own. This creates problems that stretch far beyond the realm of the crimes themselves.

Often femicides are reported as “crimes of passion,” a label that coddles and insulates the men involved from the real horror of their crimes. Initially, Páez’s case was referred to in the same way. A young boy overwhelmed and overcome by anger. This is just another way we are creating distance between men and their socially indoctrinated violence.

Ornela had this to say about the misreporting of these sensitive cases: “Antes hablábamos de crímenes de pasión, ‘La mató por celos’ o ‘No soportó que lo dejara’. Eso también es una manera de violencia simbólica. En los medios por ejemplo, banalizan lo que son los feminicidios, dicen que son crímenes pasionales, que son problemas domésticos, que son temas familiares, que no son problemas estructurales. [...] Tratan de correr la de idea de que te matan por ser mujer, y que te mataron porque tu marido se enojó o ‘es un loco’. Así se normaliza la violencia masculina.”

“Before we talked about crimes of passion, “He killed her because he was jealous” or “He couldn’t stand her leaving him’. That is also a form of symbolic violence. In the media, for example, they trivialize femicides. They say that they are crimes of passion, that they are domestic problems, that these are things you see in a family, and they aren’t structural problems. [...] They try to give you this idea that they didn’t kill her for being a woman; she was murdered because her husband was angry or he was crazy. This normalizes male violence.”

Argentinian society is imploring its women to rationalize and accept male violence. In an eerie way, it asks them to simply sit with the idea that the men they live with and love might one day snap and murder them for whatever profoundly personal reason. It is a despicable thing to ask the women of a nation to do, and more and more of them are waking up to it. “Ni Una Menos” is just one reflection of all the many important and prominent ways women are doing away with the idea that they should; “romanticize a myriad of oppressions.”

As Ornela put it, the country has hit a turning point, or at least a lot of the women have. Women have come to understand that

“No es un loco, no es un enfermo, es un hijo sano del patriarcado.”

“He is not crazy; he is not sick; he is a healthy son of the patriarchy.”

That hasn’t meant as much as many hoped in the way of actual changes. It has been five years since the “Ni Una Menos” movement began and things have yet to pivot. Femicide rates have reached a ten year high since quarantine restrictions were set within the already fraught nation. This year is set to the worst for violence against women since the nation first began to count femicides in 2012.

One of the greatest challenges faced by the movement is trying to change the heart of the nation. These narratives - the ones that encourage to accept this violence or that attempt to diminish it in hopes of ignoring their true origins are seductive. They entice us to see the world with rose coloured glasses that blind us to the realities of the violence we are seeing. But we must do away with those ideas if we hope to make any real meaningful change.

That is what FENA works so hard to do. It is about deconstructing the narratives that surround us, and giving women the power to create new ones. A lot of that is rooted grassroots activism, for and by women, but there needs to be more. Argentina is finally understanding what needs to be done, and after this horrific year there are genuine hopes that real systemic changes are on the horizon.

Art by Manu Ka, Photo by Alejandra Ruiz

In early 2020, the Argentinian government unveiled the Ministry of Women, Gender, and Diversity. The first issue the Ministry is meant to tackle is identifying the root causes of gender based violence, and devising a plan for that the government might use to prevent the issue from growing. What this ministry hopes to do, in truth, is to undo this myth of passion and fervour and identify the true cause of anti-woman violence. Their true mission, however, is to give women the confidence and freedom they need to be “juntxs y sin miedo,” “together and without fear.”

As the ministry begins its work in earnest, feminists across the country are looking on with rapt interest - eager to see what happens.

Thank you for reading! This is the latest article in a series on femicide, but we here at the Whorticulturalist encourage you to get involved in these issues. If you would like to learn more and/or donate to any of the movements mentioned here are their donation and website links:

FENA, the organisation that Ornela works for, originally began as a photography project. It has since expanded and they conduct workshops, develop and produce resources, and do the grassroots organising that helps to liberate women from the toxic notions of masculinity and violence that trap them. You can donate to them here.

NiUnaMenos is much more than just a movement, and the organisation offers lots of resources and opportunities to learn more about the situation in Argentina. They monitor femicide and lobby the government for a host of other women’s rights issues.

Hayley is an emerging writer and journalist who works hard to create work that is fiercely feminist, anti racist and anti oppression on a whole. You can check out more of her work and content on her instagram @hayley.headley

Reap what you hoe.

Sign up with your email address to receive our latest blog posts, news, or opportunities.